This beautiful specimen of Anax imperator - the Emperor Dragonfly - explored our garden pond last week and rested on this marginal plant for about a quarter of an hour. As luck would have it, at the time I was sitting outside with a mug of coffee and Pete Rollins' new book The Fidelity of Betrayal, so I could simply enjoy the sight of this magnificent insect darting about over the surface of the pond. When it landed I drew up close and was transfixed by such an exquisite example of evolutionary bioengineering. Eventually the thought of getting my camera meandered through my brain and so, despite the fairly strong breeze which was buffeting the plant, I fired off a few handheld grab shots with fill-in flash in the hope of getting at least one sharp image. And here it is. OK, so it's not as good as a DSLR with a Macro lens, but it's good enough for my purposes, which is what matters after all.

So what does the ecology of the dragonfly have to say to today's church? What analogies spring to mind? A quick peek at Natural England's helpful Dragonflies and damselflies in your garden provides a clue:

Most of a dragonfly’s or damselfly’s life – perhaps as much as 95 per cent of it – is spent in the water. The eggs, which are usually laid underwater, develop into larvae, free moving, water-dwelling nymphs, from which the flying adult insects eventually emerge. The whole process may be completed within six months, but for most species takes one or two years. In contrast to the larvae, the adults are generally short-lived.

So there are two very different phases in the life cycle of the dragonfly: the first occurs immersed in an underwater habitat until the nymph develops to the point at which it can enter the second phase, emerging into the air as an adult, to fly, feed and reproduce. One phase is effectively hidden from view, the other catches our attention. Both are essential to the continuance of the species. Now we might be tempted to lay to one side the inconvenient biological truth that dragonflies are voracious, ruthlessly efficient predators, but that would be a pity. Being effective at what you do and making the best of what you are is in some ways a tagline for the process of evolution. Why should Christianity and its churches be any different to dragonfly species and their local populations of individuals? Just as a dragonflies genes code for what it is to be a dragonfly and selection pressures over millennia tune the result for whole species, what if Christianity is meant to code for expressions of the kingdom of God? The lesson of evolutionary history is stark: species which are less effective and adaptable stare extinction in the face. Now I know that I have grossly oversimplified complex matters and drawn dodgy parallels, but there does seem to be more than a ring of truth to looking at the church in this way. Brian McLaren's cause celebre is precisely about this fundamental point: Christianity is meant to code for expressions of the kingdom of God, not church per se.

There are at least a couple of other points we might usefully ponder too. For a dragonfly nymph, being deeply immersed in one appropriate habitat / place is essential to growth and maturation. Obviously there has to be enough food and vegetation about and sufficient dissolved oxygen in the water for it to thrive. What parallels do you see here? If we think about churches we know, how appropriate as habitats are they for Christians to flourish and grow as disciples? And if the evidence is that they are not, what can be done about it? What is deficient? What is polluting? What makes for a good environment out of which mature Christians can emerge?

Then of course we are drawn back to the adult dragonfly in our garden and its genetic drive to reproduce. Relying on just one pond or watercourse would be a terribly risky strategy for a species to adopt, an evolutionary version of russian roulette. Actively looking beyond the familiarity of a particular pond for new habitats in which the species can flourish is a better strategy. Might the same be true of the church too? Remembering that Christianity is meant to code for expressions of the kingdom of God it seems obvious that we should be seeking places and contexts where mission can flourish and love can come alive. This means looking beyond the familiar local pond which we know so well. If that pond should become spoiled, the species is secure because it is present elsewhere in conditions which favour its flourishing.

So this lovely specimen of Anax imperator leaves me with much to think about. The question I now face is what shall I do with this flight of imaginative fancy? How will it inform the decisions and conversations that I will be involved in? Has my spirituality really been enriched because I happened to see a dragonfly?

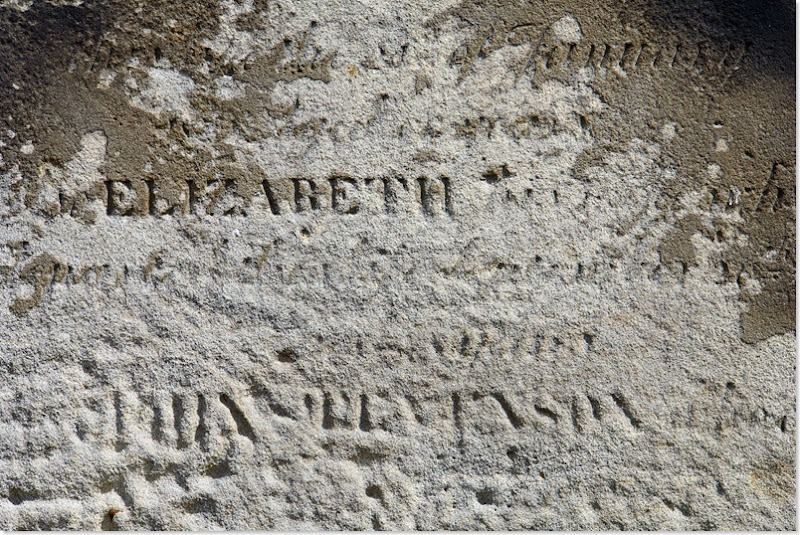

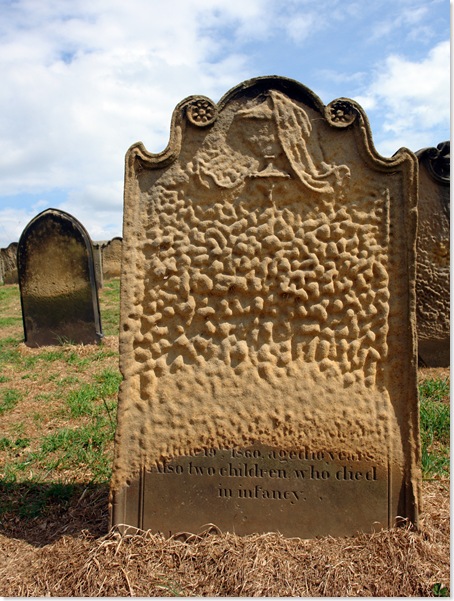

These badly weathered headstones are in the clifftop graveyard of St Mary's church in Whitby. For me there is something incredibly poignant about them. It is not just the obvious references to grief and loss, it is the sense that these lives and their unique stories are finally being erased and lost too. It seems to me that these headstones are a visual parable both of what time does to our collective memory and of the honest corrective to our human 'pomp and circumstance' which the Bible provides. Just consider these lines:

These badly weathered headstones are in the clifftop graveyard of St Mary's church in Whitby. For me there is something incredibly poignant about them. It is not just the obvious references to grief and loss, it is the sense that these lives and their unique stories are finally being erased and lost too. It seems to me that these headstones are a visual parable both of what time does to our collective memory and of the honest corrective to our human 'pomp and circumstance' which the Bible provides. Just consider these lines: