In these ecologically precarious times of climate change, environmental degradation and resource depletion, John Clare is a poet we would do well to read. From the troubled years of the early nineteenth century his authentically working class and profoundly rural voice speaks right into our contemporary dilemmas. In his lifetime the world around him was changing almost beyond recognition. Patterns of agriculture and communal village life which had pertained for centuries were being uprooted and displaced in the wake of the monstrous land grab facilitated by the Enclosure Acts. The effects of new agricultural technologies and the onset of the Industrial Revolution meant that Clare lived in an atmosphere of great upheaval and tension,

In these ecologically precarious times of climate change, environmental degradation and resource depletion, John Clare is a poet we would do well to read. From the troubled years of the early nineteenth century his authentically working class and profoundly rural voice speaks right into our contemporary dilemmas. In his lifetime the world around him was changing almost beyond recognition. Patterns of agriculture and communal village life which had pertained for centuries were being uprooted and displaced in the wake of the monstrous land grab facilitated by the Enclosure Acts. The effects of new agricultural technologies and the onset of the Industrial Revolution meant that Clare lived in an atmosphere of great upheaval and tension,  exacerbated by political revolution abroad.

exacerbated by political revolution abroad.

The landscape of Clare’s England and the lot of the rural poor was changing for ever under the hard fists of greed and privilege, wielded with such alacrity by the rich and powerful. Land which was once a common benefit was appropriated into private hands. Old ways and customs were supplanted and disrupted by fences, hedgerows and the notion of ‘trespassing’. Commodity prices were hitting the poor hard. From his rootedness in the area around Helpston and his family life in the cottage of his birth, Clare’s poetry charts the ecological, cultural and psychological impact of this socio-economic paradigm shift.

It all sounds so very modern and familiar. Communities across the globe who have to live with the impacts of Big Oil, Big Mining, Big Agriculture and Big Money will be able to empathise with the hard truths and the outrage he describes. Today the heaths and common land of his childhood are a vista of large scale commercial agriculture. Yet for all this contemporary resonance it is another aspect of Clare’s work which is especially important as, with increasing urgency, we seek an ecologically sustainable way of living together on planet earth.

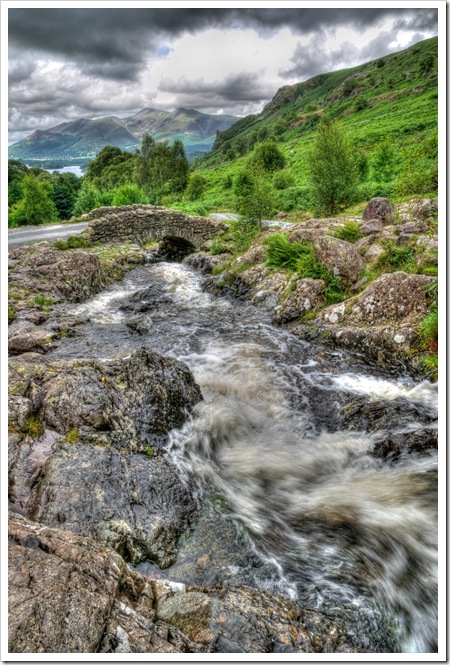

Clare was a poet enchanted by the natural world. He revelled in its detail and diversity. His was a poetry of local ecology. H e saw and valued what others might pass by without appreciation. Species, patterns, habits and habitats were his vocabulary. His solitary walks through fields, byways and woods were those of a natural naturalist wholly immersed in the intricate beauty of his environment. Here in the Sonnet ‘A Pleasant Place’ we find Clare speaking of a deep sense of blessing -communion even - which comes from such an intimately local acquaintance with nature.

e saw and valued what others might pass by without appreciation. Species, patterns, habits and habitats were his vocabulary. His solitary walks through fields, byways and woods were those of a natural naturalist wholly immersed in the intricate beauty of his environment. Here in the Sonnet ‘A Pleasant Place’ we find Clare speaking of a deep sense of blessing -communion even - which comes from such an intimately local acquaintance with nature.

NOW Summer comes, and I with staff in hand Will hie me to the sabbath of her joys,— To heathy spots, and the unbroken land Of woodland heritage, unknown to noise And toil;—save many a playful band  Of dancing insects, that well understand The sweets of life, and with attuned voice Sing in sweet concert to the pleasant May. There by a little bush I’ll listening rest, To hear the nightingale, a lover’s lay Chaunt to his mate, who builds her careless nest Of oaken leaves, on thorn-stumps, mossed and grey; Feeling, with them, I too am truly blest By making sabbaths of each common day

Of dancing insects, that well understand The sweets of life, and with attuned voice Sing in sweet concert to the pleasant May. There by a little bush I’ll listening rest, To hear the nightingale, a lover’s lay Chaunt to his mate, who builds her careless nest Of oaken leaves, on thorn-stumps, mossed and grey; Feeling, with them, I too am truly blest By making sabbaths of each common day

Tellingly Clare says that each day becomes a sabbath. Read today this becomes for me a timeless and poignant counter-cultural sideswipe at the driven nature of rampant capitalism, where time is money rather than a precious non-renewable gift.

And he mourned the degradation of his beloved landscape with a degree of feeling perhaps unmatched by any other poet. The first wordle shows part of his poem ‘The Flitting’, in which he evokes the dislocation he feels at having moved just a few miles away from Helpston. This pervasive sense of loss underscores the loss of his sanity too, which seemed to slip away just as irrecoverably as the landscape he cherished. The second wordle represents his poem ‘I Am’, written from his iconic final isolation in Northampton General Asylum.

And he mourned the degradation of his beloved landscape with a degree of feeling perhaps unmatched by any other poet. The first wordle shows part of his poem ‘The Flitting’, in which he evokes the dislocation he feels at having moved just a few miles away from Helpston. This pervasive sense of loss underscores the loss of his sanity too, which seemed to slip away just as irrecoverably as the landscape he cherished. The second wordle represents his poem ‘I Am’, written from his iconic final isolation in Northampton General Asylum.

So many of our current ecological woes stem from that estrangement from our natural environment and in cipient and disastrous disconnection between economics and ecology which became so prevalent in John Clare’s lifetime.

cipient and disastrous disconnection between economics and ecology which became so prevalent in John Clare’s lifetime.

The annual John Clare Festival in Helpston, which finished this last weekend, sees the poet’s grave adorned with posies. It is a quiet and beautiful place; somewhere to become still and listen, to pause and see.

The madness of unsustainable development may yet find its cure in the words and insight of a man who ended his days in a madhouse. The genius of John Clare, eco-poet par excellence, is a gift for our times. What we see afresh we may yet learn to value. And like Clare we live in troubled times;  and time is running out if we are to reverse the suicidal trends which are driving climate change.

and time is running out if we are to reverse the suicidal trends which are driving climate change.

So I return to the photo of the village sign in Helpston at the top of this post, and the figure sitting on the ground writing down his stream of consciousness impressions of what it is to be enfolded in the web of life. Here John Clare is carved lovingly into the common memory.

Today his words offer us the chance to carve out a respectful and sustainable way of living lightly in the world and with each other. They deserve to be read and cherished.

The ‘Northamptonshire Peasant Poet’ is how Clare  is described on the memorial to him in Helpston, which is somewhat ironically built on the site of the former village pond. Those who saw themselves as better than him, the powerful cultured elites of his day, have under the guise of progress bequeathed an enduring legacy of despoilation and degradation to succeeding generations. The time has come to celebrate the wisdom which shaped Clare’s understanding of the natural world. This is not to romanticise Clare or to disregard the benefits of technology; it is to restore a much needed sense of proportion, balance and interconnectedness to our worldview.

is described on the memorial to him in Helpston, which is somewhat ironically built on the site of the former village pond. Those who saw themselves as better than him, the powerful cultured elites of his day, have under the guise of progress bequeathed an enduring legacy of despoilation and degradation to succeeding generations. The time has come to celebrate the wisdom which shaped Clare’s understanding of the natural world. This is not to romanticise Clare or to disregard the benefits of technology; it is to restore a much needed sense of proportion, balance and interconnectedness to our worldview.

Clare’s poem ‘Summer’ expresses the wealth and richness of an ecological outlook which is beyond price. Perhaps it is in the quiet celebratory simplicity of such a ‘green’ point of view that our common future will be re-envisioned.

HOW sweet, when weary, dropping on a bank, Turning a look around on things that be! E’en feather-headed grasses, spindling rank, A trembling to the breeze one loves to see; And yellow buttercup, where many a bee Comes buzzing to its head and bows it down; And the great dragon-fly with gauzy wings, In gilded coat of purple, green, or brown, That on broad leaves of hazel basking clings, Fond of the sunny day:—and other things Past counting, please me while thus here I lie. But still reflective pains are not forgot: Summer sometime shall bless this spot, when I Hapt in the cold dark grave, can heed it not.