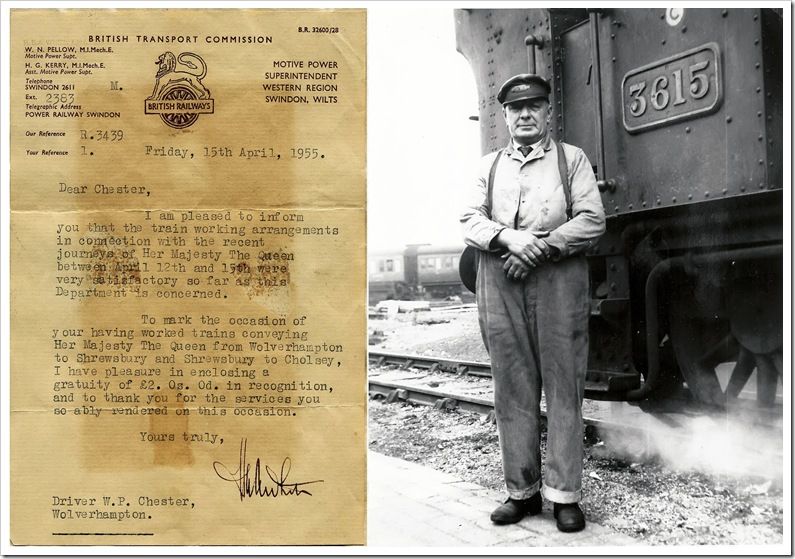

As a boy I can remember seeing this faded letter framed and in pride of place above the sideboard in my grandparents sitting room. My grandfather had been a top-link driver on the Great Western Railway at Stafford Road shed in Wolverhampton and he took great pride in having driven the royal train in 1955. Reading the text now in these postmodern times I am struck by the culture of deference which is so evident within it. Both this and the class-based social conventions of post-war Britain are long gone. Then the monarchy was still wrapped in majesty and mystique and deference was as natural as breathing. Nowadays, in our meritocratic culture, parity of esteem is the default position and we no longer depend on or defer to external sources of authority. In consequence royalty is seen much more for what it is, namely a rather curious and bizarre relic of an historically and morally dubious institution, rendered anomalous, anachronistic and absurd by the massive changes which have reshaped British society since 1955. That the terms ‘majesty’ and ‘highness’ should be applied to members of particular family and that ‘commoners’ are somehow less worthy sits badly in our celebrity-besotted and unapologetically egalitarian culture. The postmodern turn has swept away deference for good.

And I think that this goes some way towards explaining what has been happening to the churches in the 55 years since my grandfather received his £2 gratuity for driving the royal train. Once deference became passé and authority was located internally within the self it should have come as no surprise that religion was faced with a predicament. If the mystique, majesty and authority surrounding the monarchy was breaking down irretrievably, why should God and the church have fared any better? Respect was something that now had to be earned, not expected by virtue of one’s status and social standing. The radical attitudes of the 1960’s, the quest for equal rights and the struggle against inequality were here to stay. And as part of the old narrative, God and church were woven into the fabric of establishment, power and class. Citizens within a liberated society would not be told what to do or conform to norms, conventions and expectations; they would choose what they wanted to do and decide for themselves. They would no longer play the game as ‘subjects’ of the monarch in a society ordered and stratified by birthright and privilege. Religion became one commodity amongst the many that were on offer, each competing for the time and attention of secularised, emancipated ‘consumers’. Deference was well and truly dead.

So why should someone defer to God when that very model of relating was discredited and redundant? Surrendering one’s precious autonomy to a deity began to look as tenable an option as touching one’s forelock respectfully in the presence of the landed gentry. And of course the tragedy is that religion and church were bundled up with the rest of the cultural mechanisms of subservience whose power and authority had kept us in our place. What I believe is happening in the emerging church movement is the rediscovery that Christianity

is about self-giving love not self-serving power

is about service and not subservience

is about empowering people and not wielding power over them

is about choice and not imposition

is about following Jesus rather than about doing church

is about immersing ourselves joyfully in the presence of God rather than having our noses rubbed in our sinfulness

is about becoming truly human and has nothing to do with committing intellectual suicide or becoming less than we are and can be.

In other words it is all to do with living the gospel and being enlivened by the gospel. It is not about believing gobbledegook or being put down firmly in our place. The manner in which Jesus meets people in the pages of the New Testament should be music to postmodern ears. It is not old-school, old-fashioned or out of touch. Quite the reverse in fact. It feels startlingly contemporary in approach.

I think Jesus is waiting for the church to catch up with him. Perhaps he always is.

Like the bullet point summary - thanks for putting it so succinctly. I've just completed a Masters on Emerging Church and recognise each of the characteristics you mention. Brian McLaren's latest book 'A new kind of Christianity' is worth a read.

ReplyDeleteHi Ian, thanks for commenting so helpfully. I am glad to know that we are on the same wavelength about emerging church!

ReplyDelete